- Home

- Peggy Noonan

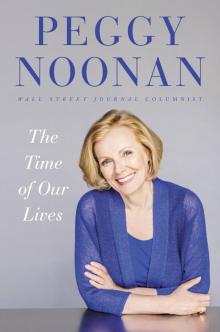

The Time of Our Lives Page 3

The Time of Our Lives Read online

Page 3

Safire had a good attitude toward his work. He loved to write, loved to mix it up, loved being part of the action. Once during the Clinton administration, during one of its scandals, he called Hillary Clinton a “congenital liar.” President Clinton said he’d like to punch him in the nose. Safire posed with a pair of boxing gloves. It was the talk of Washington. Bill loved every minute of it. I am less pugnacious than Bill—I like to write about things that are happening now so to a degree I like being in the thick of it, but I am not actually tickled by offending people. Sometimes I write tough criticisms. But deep in my heart I always hope I’m wrong, that it’s not as bad as I say it is, that there are mitigating circumstances no one knows about, facts few can see, reasons for the bad decision that make it explicable.

* * *

Here I’d like to mention something connected to my writing that came to me forcefully while I was opening the big white boxes containing my work. One of them was full of scripts and news reports I had written at CBS in New York from 1977 through 1983. As I went through them I was conscious in a new way of what those years had been for me, what I had learned and been taught.

I was immensely fortunate to be at a CBS station and then the network in the 1970s. I was allowed to become part of something new and untried, but also to benefit from something old and hallowed. Through the first I got confidence, in the second some mastery of a craft.

At the station, WEEI in Boston, we were inventing news radio—local and national news on a 24-hour cycle seven days a week. It was brand-new. I was just out of college when I arrived, and felt lucky not only to have a job in the recession of the mid-1970s but to have it in more or less the field I wanted, which was writing.

For a long time I worked the overnight, from midnight to 8 a.m. I would write, from wire copy, a top-of-the-hour broadcast for an anchorman hunched over a microphone in a little studio down the hall from the newsroom. I also spent half my shift in another small studio on the phone, taping interviews with people in the news. Mostly that meant tracking down and interviewing by phone the person who witnessed the plane crash at a local airport, or the relative of a victim of a crime. Sometimes, early in the morning, it meant interviewing a congressman or city council member. My interviews were occasionally good but mostly serviceable. I did my homework, always tried to understand the pending legislation that might be voted on that day, but I rarely grilled them or forced them off course. I really admired those young journalists who did, who could. But I was always just grateful to get the interview, and let them make the case they wanted to make. I was also a little shy in interviews, and couldn’t believe a congressman was talking to me. I was stronger as a writer, and eventually wrote the station’s editorials.

But what I learned at WEEI is that you can really write something and it gets edited and goes on the air and others hear it and actually maybe it makes some kind of difference; you can interview someone and the sound of their answers goes on the air, and maybe their answers clear something up.

I didn’t know I could do that. It was good, in my mid-20s, to learn I could.

When I went down to CBS News in New York, in 1977, my job for a long time was pretty much the same—interviews, writing morning broadcasts—but now on a network level. I was still on the overnight and still in a small space, Studio 5 at the Broadcast Center, but the interviews now were on national and international stories, and because CBS was a mighty network most of my calls were returned.

So I’m doing interviews at night and writing news shows early in the morning, and it was there, at CBS, that I really learned the essentials of what professional journalists do.

And here’s the thing: I didn’t fully understand this but I was being taught by masters.

At WEEI we’d all been young, recent college graduates. But at the network my colleagues, the radio editors and writers and anchors—were mostly veterans of the business. And some of them were great men. They taught me how to understand a story, how to tell it, how to do it clearly, in little space.

Here’s an example of my education, a small one but one that provided an insight that has guided me since.

In 1980 the Mount St. Helens volcano in Washington State erupted. It really blew, with an eruption plume that was 15 miles high; it spread ash along a dozen states.

It was my job, over those days, to call everyone I could think of nearby or in surrounding towns to do audiotape interviews about what they had seen, experienced, and what was the latest. I’d record the interview and then cut the tape down to 10 or 20 seconds of someone describing a house sliding down a hill. Telephone operators still existed, and when I ran out of local police and fire departments, I’d actually dial an operator, ask to be connected to the Mount St. Helens area code, and then mention to that operator that I worked at CBS and could she help me figure out who to talk to on this big story. More often than not the operator would be sympathetic and helpful and say something like “My cousin works at City Hall a few towns over from the volcano, you could try him.” Then she’d connect me.

One morning a week or so into the story I tracked down a guy who knew what was going on near the volcano. He didn’t have that much to say and was dryly factual, which was fine. Then, as we chatted—I had learned to chat in interviews!—he told me actually the biggest problem right now is the long lines at the post office. Why’s that, I said. Because, he said, everyone in town was picking up volcanic ash and putting it in envelopes and mailing it to their friends. The ash was slipping out of the envelopes and clogging the machines. I found this comic and lovely—how do we respond to disasters? We get mementos!—but I thought it insufficiently serious for inclusion in a sober network news broadcast so I didn’t give it to my editor to use.

Soon after, chatting in the newsroom, I mentioned it to our morning anchor, a young man named Charles Osgood, who was famous for writing the news with cleverness and wit. (He sometimes turned news stories into poems. When Mao Tse Tung’s wife was arrested and anathematized during the Chinese Cultural Revolution, he reported it in a poem that began: “Old Chiang Ching / Is a mean old thing.”

The minute I told him about the post office, Charlie’s ears perked up. Put that on top, he said.

I was startled. I thought it was just a little story that would be interesting to us. But Charles knew something interesting to us is likely to be interesting to everyone. And though it was a small anecdote it said a lot about the mood around Mount St. Helens right now: It tells us the emergency is over and human nature has kicked in. Small details add up to big pictures. He explained all this, and the lesson stayed with me.

There was something else, a great unplanned gift. In the CBS newsroom in those days there were a bunch of old, semicurmudgeonly correspondents and editors, and they taught me by reading, editing and rewriting my hourly news broadcasts. When they had time they would explain why this sentence was too long, that phrase open to different interpretation. For many years I had been a writer who wrote most comfortably for the eye. I had spent three years in college writing features and editorials for the student newspaper, and naturally wrote for readers. But the old men in the newsroom had made their careers writing for listeners, for people absorbing information not through the eye but the ear. They knew how to write words in the air, which is different from words on the page. More than that, they communicated a deeply adult sense of excitement about the gravity of news and the importance of reliable and trusted information: We can tell people what they need to know, we can actually help them understand the world better, see it clearer. They were thoughtful—this was a mission to them, a vocation—and had depth. “We have the ability to paint a big picture here—here’s your paintbrush, paint well!”

And here’s how they learned what they knew: They were the Murrow boys. They were the men who, with Edward R. Murrow, invented broadcast news. That was Eric Sevareid walking through the room checking out the wires, that was Charles Collingwood on his way to his office upstairs, that’s Winston Burdett on

the phone, that was Douglas Edwards in Studio 2. Richard C. Hottelet, Dallas Townsend. Some of them had literally been through the war with Murrow.

To me they were ancient—56! 64! Some were no longer considered at the top of their game, some hadn’t succeeded at TV, some had never wanted to leave radio for TV. I was getting the last of them. They went over my copy, x-d out the mess of the second sentence, connected the first with the third, made it all mean something important. And in time, with their guidance and almost by osmosis, I learned a great craft.

In 1981 I became the writer of Dan Rather’s daily radio commentary—which was, essentially, a daily five-minute column. And in 1984 I left CBS to go to Washington to work with Ronald Reagan. I was able to do both jobs in some part because of what I’d been taught by the men who helped invent broadcasting with Ed Murrow.

Did I know it at the time? Yes, to at least some degree. I told people of it, wrote of it. But I appreciate the luck of it more deeply now. (And I think, as I see my generation take the buyout, no, no, you must stay, you’ve got to teach the 27-year-olds what you know!)

Bonus anecdote:

I covered my first national political convention for CBS in 1980. I cannot remember where it was and I actually don’t remember if it was the Democratic or Republican convention. I remember only this: I went early, before the convention opened. I walked out onto the huge, cavernous, empty convention floor, all my credentials around my neck, excited and nervous to be there. In the room were electricians and carpenters doing last-minute work. There was one reporter, standing by himself. It was Eric Sevareid. I had not until that moment met him. He looked my way, saw the credentials of our shop, nodded. I walked over and introduced myself. He asked if it was my first time covering a convention, I said yes. He said the first time he’d covered a convention for CBS was in 1948, and he too was so excited he went early, and there was no one there in the hall but one other reporter—H. L. Mencken. Eric had introduced himself. Mencken welcomed him and put out his hand.

“Welcome,” Eric Sevareid said to me. And he put out his hand.

During the 2012 Republican convention I was on a Face the Nation, live from the floor the day before the convention started. I was navigated onto the set, over cables and past cameras, by a young producer. His name was Walt Cronkite IV. It was his first convention for CBS. I told him my story of Sevareid and Mencken.

“Welcome,” I said, and put out my hand.

* * *

Well, we should get back to the book.

It is customary in introductions to collections to write of how, when and by what process one derived one’s philosophical approach and views. I’ve written about those things over the years—you’ll find some in this book—and don’t suppose more is needed.

But I want to mention something I’ve never written of because it bears on some of the themes in this book, and animates one of them.

Regular readers know I speak often of my concerns about modern America’s culture, by which I mean the America we see all around us each day and experience as human beings. I grew up in what in my first book I called the old America, but in a relatively unprotected condition in that country. I survived to become myself because that old country was a more coherent place that, to a greater degree than now, knew what it was about.

So the story. I should say I was from a big, working-class family that was highly stressed and turbulent. We had moved when I was 5 years old from Brooklyn, New York, where I was born, to Massapequa, Long Island, and lived in that area until I was 16, when we moved to New Jersey.

Every summer when I was a child, from age 6 to age 13, I was sent, often for long stretches by myself, to stay at the home of two great-aunts in Selden, New York. Selden then, in the 1950s and early ’60s, was almost unpopulated. It had woods and flat, barren fields. (It is now a Long Island suburb full of houses and people; then it was empty.)

It was very lonely. My two great-aunts, Etta and Jane Jane, were in their 70s, which in those days was ancient and certainly seemed so to me. Etta was a former cook in private homes in Manhattan and Jane Jane was a former lady’s maid. Both were retired. Neither had had children. They were Irish immigrants, Etta a widow and Jane Jane never married.

Etta was a deeply distracted woman who didn’t much like children. I remember her as almost completely silent. She would sit at her small, oilcloth-covered kitchen table and chain smoke without inhaling, with a faraway look in her eye. I remember her saying whissshhtt for “go away” and “bad cess” of those she didn’t like; I remember her speaking often in Gaelic, the language she preferred for her sparse comments.

Jane Jane was equally distracted but also more ethereal—she recited poetry aloud—and viewed children kindly. She was kind to me and to the extent she could when nearby attempted to fill a parent’s role. She would tell me things that had happened in history. There was a sense they were still happening in her imagination. She was religious and took me each Sunday to church.

Etta and Jane Jane didn’t get along so there was a lot of silence in the house.

There was nothing to do in Selden. Every day was lonely and the nights were terrible. The little, two-bedroom house was on Sanitarium Road, which led to an old sanitarium for people with tuberculosis. It had been shut down and was now a hollow, spooky building that looked like a fortress. There was one family within walking distance, the Klines, less than a mile away, but they were not always available and they too had stresses.

I remember walking by myself in the woods and poking sticks at dead birds. I remember being fascinated by moss, and how mica shined in stones. I remember talking with Jane Jane and hearing about Woodrow Wilson, the Lusitania, and the Fourteen Points. She thought Wilson a great man who had saved Europe. At night I would get into bed with her in her little room with its little window and its bureau with pictures of the Sacred Heart. You would think sleep would be a relief after the empty days, but Jane Jane was a bit of a mystic and like most mystics had a great interest in the subject of death. To keep me company and talk me to sleep she would tell me of things like the Warning Signs of Death. She had no awareness that this might be frightening for a child; she meant only to be interesting and share what was on her mind.

She would tell me that when you are about to die a great warm mist suddenly comes over you like a dense cloud. This was Long Island in the 1950s, without air conditioning. It was 90 degrees at night. I’d listen and suddenly be bathed in sweat—the mist! My heart would race, rivulets of sweat running down my head—more mist! I couldn’t take the blanket off because another warning sign of death is that a spirit touches your hand or foot, so I had to keep them covered. Another warning sign of death: Suddenly the ticking of a clock becomes very loud. I’d suddenly hear the clock on the bureau: It was ticking like a drum!

It was all fascinating and harrowing, and I promise she had no idea. In time she’d fall peacefully asleep. I would wait until she did, creep out of bed and go into the next room where I’d put the TV on low and watch it for hours—network dramas, old movies, Jack Paar. It was all jolly or thoughtful or hopeful, representative of future life, adult life. It was comforting.

But here is the thing. Etta and Jane Jane didn’t have much, not a phone or a car, couldn’t drive, were off in that lonely place in the house in a field. But Jane Jane understood a child needs at least something to look forward to. So once a week she would take me to the big stores in Riverhead, the Suffolk county seat, 25 miles away, or to Centereach, just five miles away.

She would announce the trip in the morning, put on her thin cotton housedress, put a black wool hat on her white-haired head, take her black purse and lead me out to Sanitarium Road. And we’d stand there. And when a car or truck came by we’d flag it down. Someone would stop and Jane Jane would explain in her Irish accent, with her reedy voice, that we needed to go to the stores and would you be going to Riverhead? They’d look at us, shake their heads, sort of shrug and say, “Sure. Come on in.”

And

they’d drive us, usually all the way. Jane Jane would entertain them with stories of the Titanic and World War I, both of which had captured her imagination when she was new to America. (Her arrival here, at the beginning of the second decade of the 20th century, coincided with the invention of mass media—radio, the movies, a million newspapers. Everything she absorbed then, everything blasted into her through the airwaves and the headlines, was on her mind for the rest of her life.)

We’d get to downtown Riverhead, or Centereach, and walk around in the air conditioning of the stores. We’d do almost every one of them—clothing stores, hardware store, candy store, five and ten (Heaven) and, at the end, the ice cream counter where we’d get a Coke. The air conditioning was so wonderful. The way everything smelled—the hardware store, the counter at the ice cream part of the store—was so wonderful. It was bliss. We didn’t buy anything but you don’t have to buy when you’re a child, really, it’s enough to look, touch, get excited by what you see. Some day you’ll get it. There was a particular kindness I remember. There was a rack of magazines across from the counter in the five and ten, and they’d let you pick one up—Look , or Life, with pictures, or movie star magazines—read it while you had a Coke, and put it back when you were done. You didn’t have to pay.

And when this was over, four or five hours later, we’d decide to go home.

Here is what we did. We’d stand outside a store—the dottie old lady in the soft flowered dress and the black wool hat, the fat, unkempt little girl—and we’d wait for someone to walk by, or drive by slow. And Jane Jane would call out, in the Irish accent with the reedy voice, “We are going home to Selden. Could you be taking us?” And they’d be surprised, and look at us, and fairly soon someone would feel amazement or pity or bemusement and say yes, sure, get in, and take us back to Sanitarium Road.

The Time of Our Lives

The Time of Our Lives